CTV NEWS CHANNEL: RICHARD’S SUNDAY MORNING MOVIE REVIEWS FOR AUGUST 24!

I join CTV NewsChannel anchor Renee Rogers to talk about the thriller “Relay,” the neo-noir “Honey Don’t” and the rock doc “DEVO” on Netflix.

I join CTV NewsChannel anchor Renee Rogers to talk about the thriller “Relay,” the neo-noir “Honey Don’t” and the rock doc “DEVO” on Netflix.

Watch the whole thing HERE!

I join CTV NewsChannel anchor Renee Rogers to talk about the thriller “Relay,” the neo-noir “Honey Don’t” and the rock doc “DEVO” on Netflix.

I join CTV NewsChannel anchor Renee Rogers to talk about the thriller “Relay,” the neo-noir “Honey Don’t” and the rock doc “DEVO” on Netflix.

Watch the whole thing HERE!

I joined CTV NewsChannel anchor Roger Peterson to have a look at new movies coming to theatres, including the thriller “Relay,” the neo-noir “Honey Don’t” and the rock doc “DEVO” on Netflix.

I joined CTV NewsChannel anchor Roger Peterson to have a look at new movies coming to theatres, including the thriller “Relay,” the neo-noir “Honey Don’t” and the rock doc “DEVO” on Netflix.

Watch the whole thing HERE!

Fast reviews for busy people! Watch as I review three movies in less time than it takes to make the bed! Have a look as I race against the clock to tell you about the thriller “Relay,” the survival thriller “Eden” and the neo-noir “Honey Don’t.”

Fast reviews for busy people! Watch as I review three movies in less time than it takes to make the bed! Have a look as I race against the clock to tell you about the thriller “Relay,” the survival thriller “Eden” and the neo-noir “Honey Don’t.”

Watch the whole thing HERE!

SYNOPSIS: In “Relay,” a new thriller now playing in theatres, Riz Ahmed plays Ash, a “bribe broker” who arranges payments between corrupt corporations and whistleblowers. Mysterious and meticulous, his carefully crafted set of rules go out the window when he falls for a client, former bio-tech company employee Sarah Grant (Lily James). With a high-tech investigation team on her trail, her life is in danger unless Ash can make a deal.

SYNOPSIS: In “Relay,” a new thriller now playing in theatres, Riz Ahmed plays Ash, a “bribe broker” who arranges payments between corrupt corporations and whistleblowers. Mysterious and meticulous, his carefully crafted set of rules go out the window when he falls for a client, former bio-tech company employee Sarah Grant (Lily James). With a high-tech investigation team on her trail, her life is in danger unless Ash can make a deal.

CAST: Riz Ahmed, Lily James, Sam Worthington, Willa Fitzgerald, Matthew Maher, Victor Garber. Directed by David Mackenzie.

REVIEW: A thriller that runs headlong into its suspenseful plot, only to stumble and fall in its last half hour, “Relay” does not stick the landing.

It begins with promise. The idea of a champion for whistleblowers is an intriguing one and as we learn the ins-and-outs of how the secretive Ash runs his business, the movie earns our attention. For instance, Ash, who lives in a shadow world, faceless and nameless, communicates with his clients via the Tri-State Relay Service, which uses an operator who converts text to voice and vice versa. It’s usually reserved for the Deaf community, but, because no records are kept of the transitions Ash uses it as a tamper-proof means of exchange.

It also allows for a running joke in a rather dry movie, as the relay operators sign off every call, no matter how contentious, with “Thanks you for using the Tri-State Relay Service. Have a wonderful day.”

There’s all the stuff of classic conspiracy thrillers; pseudonyms—like Archie Leach, which was Cary Grant’s real name—secret, fortified storage lockers and tense exchanges of information.

That’s all well and good, and director David Mckenzie even stages several twitchy scenes that amp up the suspense. When a set piece in Times Square that should have been a simple exchange of information erupts into chaos, Mckenzie visually captures the chaotic, dangerous nature of Ash’s business.

Later, a concert hall sequence put me in the mind of Brian DePalma, but soon afterwards the carefully constructed cat-and-mouse game falls victim to a plot upheaval—calling it a twist is too mild a term—that is as silly as it is predictable.

It’s a shame that the same film that allows Ahmed the chance to do such layered, interesting work with minimal dialogue chooses to put such a pedestrian cap on a story that began with so much promise.

Fast reviews for busy people! Watch as I review three movies in less time than it takes to make the bed! Have a look as I race against the clock to tell you about the high kicking “Karate Kid: Legends,” the mannered “Phoenician Scheme” and the horrific (in a good way) “Bring Her Back.”

Fast reviews for busy people! Watch as I review three movies in less time than it takes to make the bed! Have a look as I race against the clock to tell you about the high kicking “Karate Kid: Legends,” the mannered “Phoenician Scheme” and the horrific (in a good way) “Bring Her Back.”

Watch the whole thing HERE!

SYNOPSIS: In “The Phoenician Scheme,” a new Wes Anderson film now playing in theatres, Benicio del Toro is Zsa-zsa Korda, a shady businessman who made his fortune through “unholy mischief.” On the verge of a new venture, he finds himself in the crosshairs, literally, of tycoons, foreign terrorists and determined assassins. “Why do you need to keep assassinating me all the time?” he asks.

SYNOPSIS: In “The Phoenician Scheme,” a new Wes Anderson film now playing in theatres, Benicio del Toro is Zsa-zsa Korda, a shady businessman who made his fortune through “unholy mischief.” On the verge of a new venture, he finds himself in the crosshairs, literally, of tycoons, foreign terrorists and determined assassins. “Why do you need to keep assassinating me all the time?” he asks.

CAST: Benicio del Toro, Mia Threapleton, Michael Cera, Riz Ahmed, Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Mathieu Amalric, Richard Ayoade, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Rupert Friend, Imad Mardnli and Hope Davis. Directed by Wes Anderson.

REVIEW: There was a time when I loved Wes Anderson’s movies. His holy trinity, “Bottle Rocket,” “Rushmore,” and “The Royal Tenenbaums,” were all unconventional gems; movies with a singular point-of-view that examined the lives of misfits and oddballs.

Then I stopped loving and stared merely liking Anderson’s movies as his signature whimsical style began to squeeze the life out of his stories of self-discovery and community. Still, his stop-motion “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” for example, was mannered but also hilarious and poignant.

These days, I long for the days of the relative restraint of “The Darjeeling Limited” and “Moonrise Kingdom.” Perhaps it’s a case of familiarity breeding contempt (although think that is too harsh a word), but to me Anderson’s films have lost the humanity of his earlier work. They still cover much of the same thematic ground, commenting on family dysfunction, failure and redemption, but they now feel as though they arrive covered in bubble wrap like precious museum pieces.

Such is the case with his latest, “The Phoenician Scheme,” a stylish story of big money, attempted assassinations and family, it features a topflight cast, who all seem to be having a swell time slotting themselves into Anderson’s carefully crafted, artisanal film. But there is an air of artificiality that settles over the movie like a shroud which sucks way much of the emotional depth.

“The Phoenician Scheme” is pretty, occasionally amusing and the commitment to deadpan performances is unparalleled, but even though I’ll watch anything with Benicio del Toro, it is more concerned with style than substance. As a result, its well-worn take on the evils of capitalism, as personified by del Toro, feels academic rather than authentic.

“Nimona,” a new sci-fi, young adult animated action-adventure now streaming on Netflix, sets its story of outsiders, identity and acceptance in a futuristic medieval kingdom where knights, on flying horse-shaped motorcycles, use old-school crossbows and high-tech gear to fight monsters.

Adapted from the webcomic by N.D. Stevenson, the story is set in a techo-medieval kingdom where the defenders of the realm, called the Institution, are knights descended from noble backgrounds dating back 1000 years. The sole exception is Ballister Boldheart (Riz Ahmed), a man of humble origins who earned his way into the Institute by relentless hard work and self-training in the art of killing monsters. His induction to the group, by Queen Valerin (Lorraine Toussaint), is turned upside down when a terrible event occurs and Boldheart is framed for the Queen’s murder.

In an effort to clear his name, Boldheart is forced to team with a shapeshifting creature named Nimona (Chloë Grace Moretz), the very trouble-making monster he had sworn to hunt and kill. She can change into almost anything—a rhino, gorilla or whale—but she sees a kindred spirit in Boldheart, and insists on being his sidekick.

“Your sidekick has arrived,” she announces. “Every villain needs a sidekick.”

“I’m not a villain,” insists Boldheart. “The real villain is still out there and I do need help.”

As Boldheart and Nimona create chaos within the kingdom and without, Ambrosious Goldenloin (Eugene Lee Yang), the realm’s champion knight and Boldheart’s love interest, is also searching for answers that will exonerate the Institution from wrongdoing. “If anyone can find them,” he says. “It’s me.”

“Nimona” bursts with imagination. The nouveau medieval, fairy tale world is wonderfully imagined, part “Henry V,” part “Bladerunner.” It’s something original, a blend of old and new, with armor-clad knights using swords that shoot lasers and other nifty artifacts with high-tech twists. The world is brought to life with visual pageantry and panache that sets the tone for the actual story.

Inhabiting this animated fantasy are characters battling very human issues. Nimona is someone who struggles with loneliness and finding a place in the world. She is an agent of chaos, a person with an appetite for destruction, but as the film’s runtime increases, so does our understanding of why she behaves the way she does. She, like Boldheart, are allegories of outsiders, characters who, within the context of the story, battle with their perception of their place in the world.

As an exploration of queerness, the film’s message of being true to yourself arises organically.

Boldheart asks her, “What would happen if you held it in?”

“I’d die,” she replies. It’s a powerful metaphoric message about being one’s self and just one of many that emphasize the movie’s LGBTQ+ themes.

“Nimona” tackles big topics, and isn’t afraid to dig deep. Sitting alongside the LGBTQ+ topics, are themes of standing up to power and how to be an ally, but it never allows the messages to overtake the story. Co-directors Nick Bruno and Troy Quane ensure that amid the messages of benevolence and self-acceptance, are plenty of emotional moments and exciting, large scale action scenes that will make your eyeballs dance.

“Flee” is a rarity, an animated documentary. A mix of personal and modern world history, it is a heartfelt look at the true, hidden story of the harrowing life journey of a gay refugee from Afghanistan.

The bedrock of this boundary-pushing doc are twenty, taped conversations Danish filmmaker Jonas Poher Rasmussen had with his childhood friend Amin (a pseudonym). As an adult, Amin is about to marry his partner Kasper when he sits down to talk to Rasmussen about how his life brought him to this moment.

He recounts how his father disappeared and his brother was conscripted to join the army in 1979 after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. As a boy, he fled his war-torn country with his mother and siblings, to find a new, safe life. They landed in Russia on a tourist visa just after the Soviet Union had fallen, leaving the country corrupt and dangerous.

Time passes. As the Russian police track him as an undocumented resident, he embarks on the most dangerous journey yet. With the help of an older brother in Sweden, Amin puts himself in the hands of human traffickers for a traumatic, uncertain journey to Copenhagen.

Except for a few minutes here and there of archival news footage, “Flee” uses animation to tell the story but this ain’t the “Looney Tunes.” Rasmussen used the animation to protect Amin’s identity, but like other serious-minded animated films like “Persepolis” and “Waltz with Bashir,” the impressionistic presentation enhances the telling of the tale. The styles of Rasmussen’s animation change to reflect and effectively bring the various stages of Amin’s journey to vivid life. It is suspenseful, heartbreaking and often poetic.

But it is Amin’s heartfelt, urgent storytelling and Rasmussen’s prodding that make the story of resilience and survival so riveting. From the grueling trek to a new land to guilelessly seeking out a cure for his homosexuality in Denmark, “Flee” proves itself as a unique work of art based on a true, traumatic and far too common refugee experience.

Reminders of real life were all around us at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. From the digital screenings we watched at home to half empty, socially distanced screenings at venues like The Princess of Wales Theatre. But when my mind wanders back to September 2021, I won’t be thinking of having to show my proof of vaccination or the social distancing in theatres.

Reminders of real life were all around us at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. From the digital screenings we watched at home to half empty, socially distanced screenings at venues like The Princess of Wales Theatre. But when my mind wanders back to September 2021, I won’t be thinking of having to show my proof of vaccination or the social distancing in theatres.

What will linger?

The images of Anya Taylor-Joy in “Last Night in Soho,” crooning an a cappella version of the Swingin’ Sixties anthem “Downtown,” and “Dune’s” Stellan Skarsgård doing his best impression of Marlon Brando in “Apocalypse Now,” come to mind immediately.

Those moments and others like them are the reason the movies exist. They transcend the vagaries of real life, transporting us away from a place where masks, vaccine passports are the reality.

And boy, did we need that this year.

Here a look back at some of the moments that made memories at this year’s TIFF:

“Night Raiders,” a drama from Cree-Métis filmmaker Danis Goulet, draws on the historical horrors of the Sixties Scoop and Residential Schools to create an unforgettable, dystopian scenario set in the new future. It effectively paints a somber portrait of totalitarian future, packed with foreboding and danger. The story is fictional but resonates with echoes of the ugly truths of colonization and forced assimilation. Goulet allows the viewer to make the comparisons between the real-life atrocities and the fictional elements of the story. There are no pages of exposition, just evocative images. Show me don’t tell me. The basis in truth of the underlying themes brings the story a weight often missing in the dystopian genre.

“Night Raiders,” a drama from Cree-Métis filmmaker Danis Goulet, draws on the historical horrors of the Sixties Scoop and Residential Schools to create an unforgettable, dystopian scenario set in the new future. It effectively paints a somber portrait of totalitarian future, packed with foreboding and danger. The story is fictional but resonates with echoes of the ugly truths of colonization and forced assimilation. Goulet allows the viewer to make the comparisons between the real-life atrocities and the fictional elements of the story. There are no pages of exposition, just evocative images. Show me don’t tell me. The basis in truth of the underlying themes brings the story a weight often missing in the dystopian genre.

I asked Danis Goulet about having many of her characters in Night Raiders speak Cree: “It is everything to me,” she said. “My dad is a Cree language speaker. He grew up speaking Cree. He learned to speak English in school. His parents were Cree speakers. And coming down to my generation, I’m no longer a Cree speaker and there are entire universes, philosophies and poetry and beauty contained in the language. When we think of where our heritage lies, maybe some people think of museums. For me I think it is in the language. I think that richness doesn’t just offer Indigenous people something. I think if others looked closer at what the language tells us about the history of this land, they would be incredibly amazed. My dad has looked at references in the language that talk about the movement of the glaciers, so, foe me to have the Cree language on screen is everything. I’m in my own process. I go to Cree language camp to try and learn back the language and the language gives back in a way that is so healing and incredible. It is one of the greatest gifts in my life. So, the opportunity to put my dad’s first language on the screen, and the language of the Northern Communities where I come from, and my language that I lost, is the best. It’s incredible.”

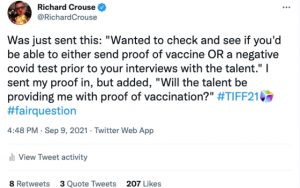

From Twitter: @RichardCrouse Was just sent this: “Wanted to check and see if you’d be able to either send proof of vaccine OR a negative covid test prior to your interviews with the talent.” I sent my proof in, but added, “Will the talent be providing me with proof of vaccination?” #TIFF21 #fairquestion 4:48 PM · Sep 9, 2021· 8 Retweets 3 Quote Tweets 206 Likes

From Twitter: @RichardCrouse Was just sent this: “Wanted to check and see if you’d be able to either send proof of vaccine OR a negative covid test prior to your interviews with the talent.” I sent my proof in, but added, “Will the talent be providing me with proof of vaccination?” #TIFF21 #fairquestion 4:48 PM · Sep 9, 2021· 8 Retweets 3 Quote Tweets 206 Likes

There is no mention of COVID-19 in the Jake Gyllenhaal thriller “The Guilty.” But make no mistake, this is a pandemic movie, A remake of 2018 Danish film “Den skyldige,” it is essentially a one hander, shot on a just a handful of set with strict safety protocols in place. Gyllenhaal, as 911 operator Joe Baylor, may be socially distanced from his castmates, but his performance is anything but distant. Played out in real time, “The Guilty” builds tension as Baylor races against a ticking clock to bring the situation to a safe resolution for Emily. Director Antoine Fuqua amps up the sense of urgency, keeping his camera focused on Gyllenhaal’s feverish performance. The close-ups create a sense of claustrophobia, visually telegraphing Baylor’s feeling of helplessness and his crumbling mental state.

There is no mention of COVID-19 in the Jake Gyllenhaal thriller “The Guilty.” But make no mistake, this is a pandemic movie, A remake of 2018 Danish film “Den skyldige,” it is essentially a one hander, shot on a just a handful of set with strict safety protocols in place. Gyllenhaal, as 911 operator Joe Baylor, may be socially distanced from his castmates, but his performance is anything but distant. Played out in real time, “The Guilty” builds tension as Baylor races against a ticking clock to bring the situation to a safe resolution for Emily. Director Antoine Fuqua amps up the sense of urgency, keeping his camera focused on Gyllenhaal’s feverish performance. The close-ups create a sense of claustrophobia, visually telegraphing Baylor’s feeling of helplessness and his crumbling mental state.

The sound of an audience laughing, applauding, crying, or whatever. Just being an audience. The big venues were socially distanced, and often looked empty to the eye, but when the lights went down and folks reacted to the opening speeches or the films, it didn’t matter. Roy Thomson Hall, with its 2600-person capacity, may have only had 1000 or so people in the seats, but for ninety minutes or two hours they formed a community, kindred souls brought together after a long break, and it was uplifting to hear their reactions.

The sound of an audience laughing, applauding, crying, or whatever. Just being an audience. The big venues were socially distanced, and often looked empty to the eye, but when the lights went down and folks reacted to the opening speeches or the films, it didn’t matter. Roy Thomson Hall, with its 2600-person capacity, may have only had 1000 or so people in the seats, but for ninety minutes or two hours they formed a community, kindred souls brought together after a long break, and it was uplifting to hear their reactions.

“Flee” is a rarity, an animated documentary. A mix of personal and modern world history, it is a heartfelt look at the true, hidden story of the harrowing life journey of a gay refugee from Afghanistan. Except for a few minutes here and there of archival news footage, “Flee” uses animation to tell the story but this ain’t the “Looney Tunes.” Rasmussen used the animation to protect Amin’s identity, but like other serious-minded animated films like “Persepolis” and “Waltz with Bashir,” the impressionistic presentation enhances the telling of the tale. The styles of Rasmussen’s animation change to reflect and effectively bring the various stages of Amin’s journey to vivid life. It is suspenseful, heartbreaking and often poetic.

“Flee” is a rarity, an animated documentary. A mix of personal and modern world history, it is a heartfelt look at the true, hidden story of the harrowing life journey of a gay refugee from Afghanistan. Except for a few minutes here and there of archival news footage, “Flee” uses animation to tell the story but this ain’t the “Looney Tunes.” Rasmussen used the animation to protect Amin’s identity, but like other serious-minded animated films like “Persepolis” and “Waltz with Bashir,” the impressionistic presentation enhances the telling of the tale. The styles of Rasmussen’s animation change to reflect and effectively bring the various stages of Amin’s journey to vivid life. It is suspenseful, heartbreaking and often poetic.

I asked “The Survivor” star Vicky Krieps about working opposite Ben Foster: “The first day I came [on set] I was very intimidated,” she said. “I wouldn’t say scared, but it felt like a wall to me. It began like this. There was no small talk. There was no, ‘How are you?’ He was already in character and it was very clear. I thought, ‘OK, I have to play his wife.’ And then, something really interesting happened. I like having a challenge and this felt like a challenge. So, I needed to find a way [to relate to him] because I knew I was going to be his wife. How do I do that? Imagine it as a wall, but then in the wall there are eyes. I used those eyes and I felt like I could open a window, and inside of those eyes was a horizon where I could go. I liked to say to Ben, ‘And then we would dance.’ Sometimes I wrote to him and said, ‘It was nice dancing today.’”

I asked “The Survivor” star Vicky Krieps about working opposite Ben Foster: “The first day I came [on set] I was very intimidated,” she said. “I wouldn’t say scared, but it felt like a wall to me. It began like this. There was no small talk. There was no, ‘How are you?’ He was already in character and it was very clear. I thought, ‘OK, I have to play his wife.’ And then, something really interesting happened. I like having a challenge and this felt like a challenge. So, I needed to find a way [to relate to him] because I knew I was going to be his wife. How do I do that? Imagine it as a wall, but then in the wall there are eyes. I used those eyes and I felt like I could open a window, and inside of those eyes was a horizon where I could go. I liked to say to Ben, ‘And then we would dance.’ Sometimes I wrote to him and said, ‘It was nice dancing today.’”

“Last Night in Soho,” from director Edgar Wright, is a love letter to London’s Swingin’ Sixties by way of Italian Giallo. Surreal and vibrant, and more than a little bit silly, its enjoyable for those with a taste for both Petula Clarke and murder. It begins with verve, painting a picture of a time and place that is irresistible. A mosaic of music, fashion and evocative set decoration, the first hour brings inventive world building and stunning imagery. Wright pulls out all the stops, making visual connections between his film and the movies of the era he’s portraying and even including sixties British icons Rigg, Tushingham and Stamp in the cast.

“Last Night in Soho,” from director Edgar Wright, is a love letter to London’s Swingin’ Sixties by way of Italian Giallo. Surreal and vibrant, and more than a little bit silly, its enjoyable for those with a taste for both Petula Clarke and murder. It begins with verve, painting a picture of a time and place that is irresistible. A mosaic of music, fashion and evocative set decoration, the first hour brings inventive world building and stunning imagery. Wright pulls out all the stops, making visual connections between his film and the movies of the era he’s portraying and even including sixties British icons Rigg, Tushingham and Stamp in the cast.

I asked “Dune” star Rebecca Ferguson why she said reading Frank Herbert’s novel was like doing a crossword puzzle: “Sometimes I wonder what comes out of my mouth,” she said. “My mother and many of my friends sit and do crosswords, but I have never been in that world. There is a way of thinking around it. It’s logical, mathematical. You need to be able to see rhythms. Whatever it is. Reading “Dune” was quite dense and I think for people who are immersed into the world of science fiction, they understand worlds and Catharism and this planet and that planet. It is just another picture, which, not to stupefy myself, I am intelligent enough to understand it, but there is a rhythm. I think it is me highlighting the fact that people who live and breathe science fiction, they get it at another level.”

I asked “Dune” star Rebecca Ferguson why she said reading Frank Herbert’s novel was like doing a crossword puzzle: “Sometimes I wonder what comes out of my mouth,” she said. “My mother and many of my friends sit and do crosswords, but I have never been in that world. There is a way of thinking around it. It’s logical, mathematical. You need to be able to see rhythms. Whatever it is. Reading “Dune” was quite dense and I think for people who are immersed into the world of science fiction, they understand worlds and Catharism and this planet and that planet. It is just another picture, which, not to stupefy myself, I am intelligent enough to understand it, but there is a rhythm. I think it is me highlighting the fact that people who live and breathe science fiction, they get it at another level.”

“Dune,” the latest cinematic take on the Frank Herbert 1965 classic, now playing in theatres, is part one of the planned two-part series. “Dune” is big and beautiful, with plentiful action and a really charismatic performance from Jason Momoa as swordmaster Duncan Idaho. It is unquestionably well made, with thought provoking themes of exploitation of Indigenous peoples, environmentalism and colonialism.