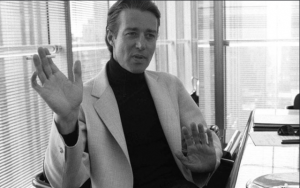

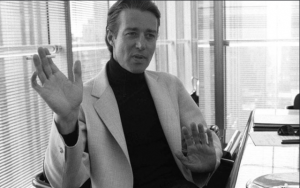

He was once the single most successful American fashion designer ever, a man who counted Andy Warhol and Liza Minelli among his best friends. Studio 54 was his playground and he made Pill Box hats a sensation after designing one for Jackie Kennedy. He was Halston, a pioneer, nearly forgotten today.

He was once the single most successful American fashion designer ever, a man who counted Andy Warhol and Liza Minelli among his best friends. Studio 54 was his playground and he made Pill Box hats a sensation after designing one for Jackie Kennedy. He was Halston, a pioneer, nearly forgotten today.

From his early days as head milliner at Bergdorf Goodman to his stunning late 1960s success to his domination of the 1970s, he defined what was fashionable for the in-crowd. “He took away the cage,” says former “Halstonette” Pat Cleveland. “He made things as though you didn’t really need the structure as much as you needed the woman.” He designed luxurious pieces from single pieces of material, usually silk or chiffon, doing away with the extras like bows and zippers, creating form fitting clothes that, as Minelli says, “danced with you.” His clothes were for a modern time when women’s lives had changed and they were very popular. “You were free inside your clothes,” says model Karen Bjornson.

In 1973 he created a sensation presenting a runway show at the Palace of Versailles, which made him one of the first American designers to rock the world of Parisian couture. Minelli says the staid audience were wowed by the show. “They went bananas. All that energy and that joy and that wonder and that curiosity. That is America.” Years later he made similar inroads in China, breaking through in a way none of his contemporaries were able to emulate.

The ambitious designer’s company was growing as quickly as his acclaim. Money came in the form of business deals with Norton Simon holding company that also owned cosmetics giant Max Factor and a disastrous deal the down market JCPenney. One reporter labels the deal, “from class to mass,” and it marks the decline of Halston’s empire.

French filmmaker Frederic Tcheng is a specialist in the genre of fashion docs. He previously directed “Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel” and co-produced and co-edited the feature “Valentino: The Last Emperor.” It’s a world he understands and the kind of story he is expert in telling. For the most part his instincts don’t let him down here. He doles out the details, carefully weaving together the personal and professional story of a man whose career was destroyed by excess—he spent $2000 to $3000 a week on cocaine—and compromise.

Tcheng ‘s choice to use a framing device, an unnamed narrator played by fashion blogger Tavi Gevinson, posing as an employee in the Halston archives feels like an unnecessary addition given the natural, dramatic rise and fall of the story.

“Halston” is part biography of a creative genius, part cautionary tale for artists who throw their hats in the ring with big corporations and lose everything, including the right to use their own name.

Richard joins CP24 anchor Nathan Downer to have a look at the weekend’s new movies including the Elton John fantasy flick “Rocketman,” the foot-stompin’ “Godzilla: King of the Monsters” and the fashion documentary “Halston.”

Richard joins CP24 anchor Nathan Downer to have a look at the weekend’s new movies including the Elton John fantasy flick “Rocketman,” the foot-stompin’ “Godzilla: King of the Monsters” and the fashion documentary “Halston.”