THE CAPOTE TAPES: 3 ½ STARS. “compelling portrait of a pioneer.”

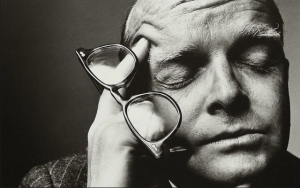

Truman Capote was the best-known literary writer of his day. The author of “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and the world’s first nonfiction novel “In Cold Blood” was as famous for his nasally voice and trading bon mots with Johnny Carson as he was for his perfectly crafted prose. A new documentary, “The Capote Tapes” from director Ebs Burnough, dives deep to examine the man behind the talk show clips.

Truman Capote was the best-known literary writer of his day. The author of “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and the world’s first nonfiction novel “In Cold Blood” was as famous for his nasally voice and trading bon mots with Johnny Carson as he was for his perfectly crafted prose. A new documentary, “The Capote Tapes” from director Ebs Burnough, dives deep to examine the man behind the talk show clips.

He was, by depending on who you ask a, “candied tarantula,” a charmer with a sharp tongue, or “the most lionized writer since of Voltaire.” His combination of wit and unfettered commentary—”He’s a marvelous performer,” Capote says of Marlon Brando, “but he’s so dumb it makes your skin crawl.”—made him a one-of-a-kind, even in jaded world of New York City high society. “You looked forward to seeing him because you knew it was nobody else like him,” says Lauren Bacall.

Capote died early, at age 59, but left behind a well-documented life. Burnough uses a combination of archival footage, TV appearances, stills and, most importantly, previously unheard audio interviews George Plimpton conducted for a book he never wrote. Some of the footage will look familiar to Capotians, particularly the well documented 1966 Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, but the audio tapes are exciting and provide new insight.

Interview subjects like Capote’s pal Dotson Rader dig deep, offering up suggestions that the writer never felt loved even though he was adored by millions. Norman Mailer describes Capote’s courage in living as an openly gay man in a repressed era.

The coverage of his literary career, particularly the “In Cold Blood” saga—Capote may have allowed himself to become too close to the story’s subjects—covers familiar ground. It isn’t until the film’s latter half when it explores the writing of “Answered Prayers,” Capote’s ten-years-in-the-making novel on New York’s not-so-polite-society that Burnough tills new ground.

The book was never finished, although he did manage to pound out three chapters of gossipy secrets about his closest friends before his death. Published in excerpts it was reviled as a literary work and destroyed the goodwill Capote had built among the wealthy women he called “his swans.” It was the end of Capote as a great writer and raconteur, and soon he soon lost the battle with booze and drugs.

Was the book simply ahead of its time? Was it Capote’s prescient unveiling of the tell-all celebrity culture that would soon become the norm by way of reality television or was it a misguided attempt at exposing the world around him? The film leans toward the former, but Jay McInerney, interviewed at length, suggests we’ll never know for sure. He’s convinced the book was never finished.

“The Capote Tapes” is a compelling portrait of a pioneer, a brilliant gay man who came from humble beginnings to rise to the top of the literary world on his own terms, even if those terms were ultimately his undoing.