Thanks Hit Parader… or How I learned to stop worrying and love the Ramones

The mid-seventies were a confusing time to be a music-obsessed kid looking to latch onto pop culture in Nova Scotia.

The mid-seventies were a confusing time to be a music-obsessed kid looking to latch onto pop culture in Nova Scotia.

Old hippies weren’t my people—they were everywhere, sporting peace and love hangovers, tie dyed t-shirts and dazed looks. With them came bad hygiene and battered copies of Aoxomoxoa. The free love stuff sounded pretty good to me, but I never liked Birkenstocks and stoner rock wasn’t my thing, (although Silver Machine by Hawkwind was usually worth a fist pump.)

In syncopated lockstep with the 60s leftovers were the disco Dan’s and Dani’s, polyester-outfitted goodtime seekers looking to boogaloo to the top of Disco Mountain. I did the Bump at school dances, I suppose, and played the hell out of my Jive Talkin’ 45, but I was six three at age twelve so wearing platforms were out of the question. Even if I could have worn them the hedonistic woop-woop of disco felt alien to me, like it was emanating from a different planet where everyone had glittery skin and mirror balls for eyes.

Singer songwriters wrote about things that didn’t touch me. 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover? I didn’t have a lover to leave once, let alone another 49 ways. Also, lover? Who did Paul Simon think I was? Marcello Mastroianni?

Country rock was OK, although at nine plus minutes Freebird overstayed its welcome by about six minutes. Country music was for hillbillies (it wasn’t until much later I discovered the joys of Waylon and Willie and the boys), soft rock was for girls and I’m pretty sure only dogs could fully appreciate Leo Sayers’ high-pitched wailing. I liked KISS although their “rock and roll all night, party everyday” ethos seemed unrealistic, even to a teenager.

My parents listened to the smooth sounds of Frank Sinatra which frequently clashed with the hard rock racket emanating from my brother’s room.

I was left somewhere in the middle.

Of course I had records. A stack of them.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars was usually near the top. It was a touchstone then as it is now because of its exceptional songwriting, cool cover and otherworldly sounds. I also had the obligatory copy of Frampton Comes Alive! but I also had pop records, heavy metal albums and some disco. But I hadn’t yet heard the definitive sound. For my brother it was Jimi Hendrix’s string stretching. For my dad it was Bing Crosby‘s croon.

I was fifteen and hadn’t yet passed that most important—to me anyway—rite of passage: finding the combination of notes and attitude my parents wouldn’t understand.

In those days the top ten charts were really diverse and fans were regularly exposed to a baffling array of music. The Billboard charts hadn’t yet fragmented off into genre specific listings and radio wasn’t yet run by robots with limited imaginations. Playlists were all over the place, and if you weren’t quick on the dial you’d awkwardly segue from the slick jazz of George Benson into You’re the One That I Want’s pop confectionary.

There weren’t many stations were I grew up but there was a smörgåsbord of sounds to be heard, but around the time Barry Gibb became the first songwriter in history to write four consecutive #1 singles on Billboard’s Hot 100 Chart the music on the radio started to have less appeal for me.

On the quest to figure out your identity there are few things more soul destroying for a fifteen-year-old than finding yourself inadvertently humming along to a song on the radio as your dad drives and hums in harmony.

I didn’t want the shared family something-for-everyone experience radio offered. I wanted my own experience so I began to regard the radio I grew up listening to as Musicology 101. With its indiscriminate playlists, it’s ability to embrace all genres I had a solid base to build on, but like many good relationships we outgrew one another.

Songs by Kenny Rogers and the like were everywhere but tunes such as The Gambler sounded hopelessly old fashioned; like a Zane Grey dime store novel put to music. So when the radio, which had been my constant companion, fell away as a source of discovering new music I turned to Hit Parader, Circus, Cream and any other magazine I could to find out what was what.

There I saw pictures of the Comiskey Park Disco Demolition Night that lead to the jettisoning of my Bee Gees singles. I read about Elvis Presley dying on the toilet, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s plane bursting into flames, killing six while, ironically, promoting the Street Survivors LP.

It felt like the old guard was fading away. Sure Queen (liked them) and Barry Manilow (not so much) and Village People (see Manilow note) were still having hits, and Bruce Springsteen was still being loudly touted as the future of rock and roll (by rock critic turned Bruce’s co-producer Jon Landau who wrote, “I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.”) but I wasn’t ready “to trade in these wings on some wheels.”

At the same time my one-time hero Alice Cooper got sober and made the worst record of his career to date but that stuff was quickly fading as I began to hear about—but not actually hear—some exciting music from London and New York.

The only thing I knew about New York came from TV and a family from Manhattan who rented a cottage every year at one of the three beaches that framed my hometown. They told me that if you left your bike unchained at the corner of Ninth Street and Second Avenue it would disappear almost immediately, as if by magic.

London I knew only from history books, James Bond and Monty Python.

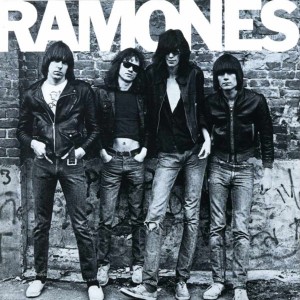

But in the pages of my mags I learned about a new youth movement, a musical incubator spearheaded by bands like The Ramones, The Clash, Wire and Television.