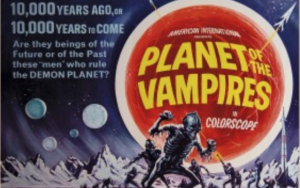

HALLOWEEN WEEK 2021: PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES “My aim is to scare people.”

Astronaut number one: “What’s going on?”

Astronaut number one: “What’s going on?”

Astronaut number two: “I wish I knew.”

— Dialogue from Planet of the Vampires

“People, and critics too, should know about the circumstances under which I had to shoot my films,” said Mario Bava. “On Terrore nello spazio (Planet of the Vampires) I had nothing, literally. There was only an empty soundstage, really squalid, because we had no money. And this had to look like an alien planet! What did I do then? I took a couple of papier-mâché rocks from the nearby studio, probably leftovers from some sword and sandal flick, then I put them in the middle of the set and covered the ground with smoke and dry ice, and darkened the background. Then I shifted those two rocks here and there and this way I shot the whole film.”

Planet of the Vampires is a low budget film, but the visual style of Italian maestro Mario Bava elevates what could have been a forgettable B-movie into a memorable movie experience.

American International Pictures, the house that entertainment lawyer turned Hollywood showman Samuel Z. Arkoff built by churning out cheaply-produced exploitation films with grabby titles like I Was a Teenage Werewolf and Invasion of the Saucer Men, had distributed two of Bava’s best known films, 1960’s terrifying fairy tale Black Sunday and ’63’s Black Sabbath (Ozzy Osbourne and friends lifted their band’s name from this movie).

Those films had filled AIP’s coffers, so Arkoff and collaborator, James H. Nicholson felt it was time to co-produce a movie with Bava, rather than simply distribute the finished product. They’d make more money and be able to shape the story according to the ARKOFF Formula, which was the former lawyer’s recipe for B-movie success.

- Action (exciting, entertaining drama)

- Revolution (novel or controversial themes and ideas)

- Killing (a modicum of violence)

- Oratory (notable dialogue and speeches)

- Fantasy (acted-out fantasies common to the audience)

- Fornication (sex appeal, for young adults)

AIP provided the services of Robinson Crusoe on Mars screenwriter Ib Melchoir to help form the “haunted house in space” tale based on the short story One Night of 21 Hours by Renato Pestiniero into a screenplay.

An international cast was assembled, headed by American Barry Sullivan, Brazilian actress Norma Bengell, Italian starlet Eva Marandi and Spanish actor Angel Aranda. Co-writer Robert J. Slotak remembers it was a confusing shoot, with each cast member using “their own native tongue on the set, in many cases not understanding what the other actors were saying.”

Sullivan plays ever-so-serious Captain Mark Markary of the exploratory space ship Argos. In orbit over a newly discovered planet, the fogbound Aura, the Argos begins receiving odd electronic signals. Forced to crash land on the desolate planet by a radiation overload, the troop turns on one another. Once restrained, the aggression disappears and the crew members have no memory of their violent behavior.

Markary, puzzled by the feral behavior of his crew, doesn’t have time to get to the bottom of the mystery before he receives a distress signal from their sister ship, the Galliot. Leading a small search and rescue party Markary braves a hallucinatory landscape of psychedelic swirling colors and molten lava flows only to find that most of the Galliot’s crew has already massacred one another, and those who survived are badly injured, and worse, most of the scars are psychological. In other words, they’ve gone crazy from fear.

It’s a grim discovery, made all the worse when it is revealed that the deceased Galliot crew members are having a hard time staying dead. In one of the film’s most eye-popping sequences the undead rise from their makeshift graves with a taste for living flesh.

Bava, working with no money but lots of ingenuity isn’t so much a cinematographer as he is a Cinemagician. For once, Arkoff’s penny-pinching ways actually served the movie. Optical special effects are expensive so Bava created the world of Aura using nothing but miniatures and old-school forced perspective shots. The two papier-mâché rocks — “Yes, two,” he said years later, “one and one!” — were maximized with the use of mirrors and multiple exposures to give the illusion of a rocky landscape. It’s hard to know for sure, but it’s possible that if Bava had access to a larger bank roll he might not have been so imaginative in his execution of the look of the film.

As much as possible the special effects were done “in camera,” that is utilizing the camera’s operations such as stop motion, slow shutter tricks and multiple exposures in lieu of special effects which are typically added to the film once the shooting is complete.

Bava further masked the cheapness of the set with a rainbow of colored lights filtered through fog. “To assist the illusion I flooded set with smoke,” he said.

It’s this sense of style that makes Planet of the Vampires so enjoyable. Bava injects great atmosphere into every frame, literally turning a sow’s ear into a silk purse. The film’s simple B-movie premise doesn’t promise much in the way of originality, but Bava’s unerring eye elevates the material, giving us an alien world unlike any seen on film to date.

Fangoria’s Tim Lucas wrote, “Planet of the Vampires is commonly regarded as the best SF ever made in Italy, and among the most convincing depictions of an alien environment ever put on film.”

The images are striking, none more so than the scene where the Argos astronauts discover a derelict ship in a huge ruin on the strange new planet’s surface. Climbing through the skeleton of the ship they uncover the gargantuan remains of mysterious creatures. If this sequence looks familiar, it’s perhaps because it appears that Ridley Scott borrowed from it while shooting Alien. Although Scott and screenwriter Dan O’Bannon deny having ever seen Planet of the Vampires at the time they made their film, the similarity between Bava’s vision and a long sequence in the 1979 movie cannot be disputed.

Bava died in 1980, and even though he made all kinds of films during his career, his name has become synonymous with horror. It’s ironic that the maker of such classic horror films as Kill, Baby . . . Kill and Twitch of the Death Nerve was a bit of a fraidy cat in real life.

“I make horror movies,” he said,” my aim is to scare people, yet I’m a fainthearted coward; maybe that’s why my movies turn out to be so good at scaring people, since I identify myself with my characters . . . their fears are mine too. You see when I hear a noise at night in my house, I just can’t sleep . . . not to mention dark passages. Sure, I don’t believe in vampires, witches and all these things, but when night falls and streets are empty and silent, well, sure I don’t believe . . . but I am, frightened all the same. Better to stay home and watch TV!”