Aviation films still fly In Focus by Richard Crouse METRO CANADA Published: January 18, 2012

The first Best Picture Oscar winner was Wings, a 1927 aviation flick featuring an inane love story but some spectacular aerial footage.

The first Best Picture Oscar winner was Wings, a 1927 aviation flick featuring an inane love story but some spectacular aerial footage.

Director William A. Wellman used his experience as a celebrated combat pilot during World War I to create the movie’s realistic and thrilling dogfights, which packed audiences into first-run theatres for 63 weeks straight.

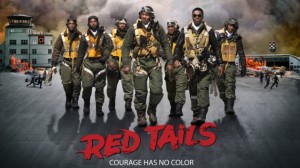

George Lucas, the producer of this weekend’s Red Tails, must be hoping for similar success for his aviation movie. If Red Tails draws crowds, he says, he wants to expand the story of African American World War II pilots the Tuskegee Airmen into a trilogy.

Advance word suggests Red Tails’ air battles are amongst the best ever created on film. Perhaps so, but Lucas has 100 years of elaborate aerial photography to compete with.

The flying sequences in Battle of Britain, the 1969 recreation of the British RAF’s defeat of the Luftwaffe, are regarded as the gold standard of aviation footage. To shoot these spectacular scenes the filmmakers assembled such a large collection of vintage planes that the production briefly became the 35th largest air force in the world.

But not all the planes were authentic. Mock-ups of Spitfires and Hurricanes, powered by lawn mower engines, can be seen taxiing down runways.

Shooting complicated stunt scenes always involves risk, but rarely has a movie been as deadly as Howard Hughes’s aerial epic Hell’s Angels.

The eccentric Hughes shot the movie as a silent film in 1928, and then reshot the entire thing the following year when sound equipment became available. In the process, 70 WWI aces were used, and three were killed. Hughes himself was injured when he crashed after performing a tricky aerial stunt.

The most famous aerial movie of recent years has to be Top Gun. Inspired by a California magazine story about the U.S. Navy’s Top Gun School, the movie used several real aircraft from F-14 fighter squadron VF-51 Screaming Eagles. The planes cost the production $7,800 per hour for fuel and other operating costs, and one shot cost three times that.

Legend has it that director Tony Scott wanted to film an aircraft landing on an aircraft carrier, backlit by the sun. The captain, however, changed course before Scott got his shot. When the director was informed it would cost $25,000 to turn the ship around Scott pulled out a chequebook, wrote the cheque and got his shot.